How technology startups change the B side of healthcare.

Digital health applications significantly impacted healthcare delivery, care navigation, and remote patient monitoring during the pandemic. Rapid adoption and expansion attracted enormous growth capital, and mega-funding rounds were making weekly headlines.

Although these virtual care startups are well-capitalized, opportunities still exist, given how much the companies have achieved compared to the size of the problems they’re respectively tackling. The rising virtual care also created challenges and opportunities on the infrastructure layer, from data interoperability to revenue cycle management.

One of the questions our team has been asking ourselves has been, “virtual care delivery has become a major category in the space. How can we help these companies to scale?” After some research, the question goes beyond virtual care as “about 50% of the physicians in the U.S still work for themselves. How can we help them?” The two practicing models are related since, regardless of the type of practice, the administrators must deal with various back-office operations that impact the financial outcomes of a business.

Looking back over the past decade, we’ve witnessed many combinations of business model innovations and software applications to make healthcare operations and service distributions more effective. While the trend continues, we believe further automation will be built upon the structured data within the existing legacy systems.

SaaS marketplace in B2B automation - applying what works in an under-teched sector.

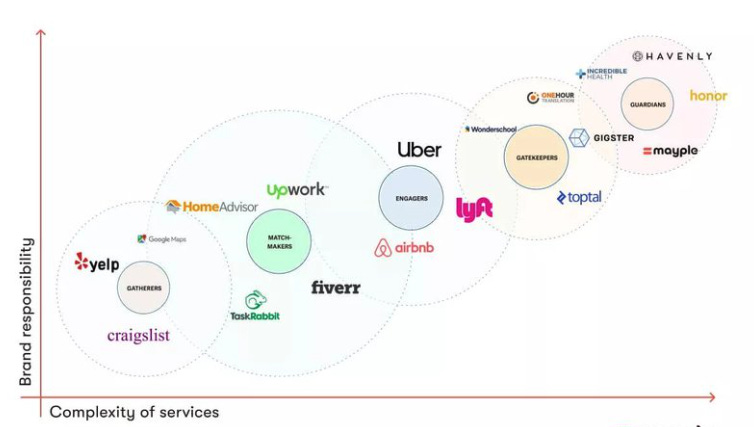

The SaaS-enabled marketplace model, a.k.a. managed marketplace, has penetrated various business verticals from transportation, hospitality, and construction to fashion. In those business models, a controlled entity can own consumer trust quickly through an established brand while leveraging the software component for quality assurance. Such effects are rooted in our daily lives as much as we’d replace an action (verb) with the company’s brand name. E.g., “I am going to Uber.” And “We’d AirBnB.”

The multi-side product value proposition creates monetization opportunities for transactions flowing through each platform. For instance, Uber and AirBnB disrupted transportation and hospitality by connecting gig workers and property owners to travelers. Others include Opendoor for home sales and Poshmark for goods labeling.

The fundamentals of the business model seem straightforward - applying a SaaS stack to standardize what used to be labor-intensive in service industries. It benefits all stakeholders (customers) by aggregating supply and demand, removing operational fragmentations through various levels of workflow automation, and improving communications and collaborations between parties.

(Such a marketplace sometimes restrains suppliers’ flexibility in negotiation due to controlled economics, so suppliers would become the price takers, e.g., Uber. It could be confusing when startups call themselves a managed marketplace when they put efforts into recruiting. And in healthcare, it could be practitioners who work under 1099s.)

So, what about healthcare?

GoodRx, an example, launched its telehealth marketplace right after COVID-19 stormed the world. The company assists telehealth partners with a part of their prescribing workflow.

GoodRx also has a strong brand effect. By 2020, there were 17M Americans using the platform monthly. Fortunately, I am still not their target demographic yet. Though based on the fact that many early-stage virtual care startups I’ve spoken with were excited about the potential to join the marketplace, it entails how powerful GoodRx’s consumer traffic can be to those companies.

Also, nurse burnout has been one of the biggest challenges in the U.S and peaked during the pandemic; there were 3M registered nurses in the U.S while the workload could take 4M to fulfill. That has become a chronic problem alongside the aging population. Recently, the undersupply of skilled laborers has created three billion-dollar nurse staffing startups within 12 months apart (Nomad Health, Incredible Health, and IntelyCare) plus one another (Trusted) at a similar scale.

While healthcare systems compete in the workforce, companies like Incredible Health use software AI to help the recruiter prescreen and vet candidates. That speeds up the recruiting feedback loops for healthcare organizations and saves nurses time searching for the right jobs.

The list can go on and on, from innovative benefit plans (Sidecar Health) to home care coordination (Hornor). But again, the common characteristics of these marketplaces are 1) to allocate and distribute resources more efficiently, 2) to use software to improve quality control, and 3) to have business customers on at least one side of the marketplace.

A slow pace in automation indicates big opportunities.

If the marketplace model in healthcare is nothing new, what about the manual tasks that no one likes but hasn’t been addressed, at least not at scale?

Historically, healthcare adoption of technologies has been much slower than other industry vertices. The HITECH Act pushed the boundary of clinical digitalization in 2009, yet until the pandemic, there were very few innovations beyond prettier UIs embedded in the EHRs. And healthcare professionals (HCPs) manually enter the data into the legacy systems.

Using billing and coding as an example, the standardization of data entry is an improvement by removing inconsistencies in pen and paper, e.g., Kareo and Dr. Chrono. However, most work still relies on human inputs, from billers entering patients' information to coders collaborating with practitioners on code assignments.

The reimbursement system in the U.S is complicated and has a significant impact on clinical burnout. When compared to the counterparties in Canada, U.S physicians and healthcare administrators spend 4x as much on administrative work. Yet, 4 out of 5 medical bills still contain errors.

Even if the bills get through the clearing houses, insurance companies can still deny them based on how a practice manages the documentation or the explanation of benefit mismatch in the services. The denials can also be due to miscommunication between patients and the stakeholders during a heavy manual pre-authorization process, leading to consumer bankruptcy when expensive procedures are performed.

Is now the right time to automate the labor-intensive workflow by leveraging more robust software applications?

The prevalence of MSOs - Management Service Organizations

Over the past few decades, MSOs (Management Service Organizations) have played an increasingly critical role in practice management.

An MSO is a business entity that provides non-clinical services to physician groups, and it may specialize in a single service type or provide a variety of administrative assistance. It can be dedicated to one care specialty or serve multiple specialties. Partnering with MSOs allows physicians to cut back on administrative burdens, so they can focus on treating patients.

MSO gained popularity in the early 1990s as managed care began driving down reimbursements and encouraging physicians to be in-network for effective care coordination. That triggered the wave of two-decade consolidation, which is still ongoing. After we entered the 21st century, MSO growth slowed because of technology implementation problems across multiple sites.

Fast forward to the 2010s, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was introduced to combat rising care costs further. Undoubtedly, the ACA has made clinical administration even harder to manage within small groups, e.g., the health IT regulation and the value-based care operations. And MSOs have never been more important in assisting physicians’ daily operations than before.

Suppose physicians in the same zip code were competitors back in the day. They now have to collaborate more closely for cost and care quality considerations after the series of care model innovations.

MSOs can also be valuable vehicles for physicians-owned practices to acquire or partner with each other, scale services, and achieve a larger economy of scale. That also explains the recent influx of PE clinic rollup activities.

Digital “MSOs” - the Shopify for digital healthcare

While telehealth was helping the system to solve the unexpected public health challenges over the pandemic, a whole stack emerged for virtual-oriented practice administration.

Companies in this category include Steady MD, Wheel, OpenLoop Health, and more. Unlike the virtual specialty care startups that built many of the technologies internally in the early days, these companies offer end-to-end solutions primarily for primary care physicians and groups to launch their telehealth practices.

Compared to traditional brick-and-mortar practices where tangible assets and face-to-face interaction restrict practice scalability, the virtual first nature allows providers and software vendors to expand much more quickly. The early-mover advantage grants the companies the ability to build a strong brand in that domain, yet other companies that start with one part of the workflow can also add product offerings to compete with them, e.g., Healthie, Elation Health and Canva Medical.

What about turning a digital MSO into a marketplace where the entity facilitates transactions between providers and payers?

The MSOs allowed private equity firms to roll up medical practices by bypassing the CPOM doctrine, and it’s also widely adopted by the mid-layer digital healthcare companies to partner up with practitioners who are normally hired under 1099s or W2s by the virtual care companies. That benefits digital MSOs by encouraging physicians to deliver high-quality care without taking the risks of physical asset ownership.

As professionals working in health tech, everyone knows more or less about managing patients. The physicians and administrators know the most about how hard it is to manage the payor relationships. That’s why IPAs (Independent Providers’ Associations) exist to act as the front office roles. More importantly, an IPA at scale can also assemble its own MSO, the back office, to save SG&A expenses for its members.

The early trend is already seen in mental health, e.g., Headway, Grow Therapy, Alma, etc. Besides acting as digital specialty care MSOs, the companies are also “marketplaces” and intermediaries for contract aggregation. Now, therapists on these platforms no longer need to manage the administrative work manually, like tracking different insurance contracts, and can acquire patients in volume through referrals.

My two cents on why mental health digital MSOs are moving quicker than their peers in primary care are that;

Virtual care can be the sole delivery model for certain mental health disorders, whereas primary care would require face-to-face visits for things like physician examinations.

The typical mental health operation is more straightforward than primary care, e.g., fewer reimbursement codes.

I’d imagine that for companies like Wheel to operate in similar manners would need back-and-forth conversations with payors regarding the scope of coverage, the terms, and the networks. On the other hand, Firefly offers value-based benefit plans to employers while partnering with hospitals for face-to-face visits.

Looking for the unmet needs

We reviewed how the existing marketplaces impact the business side of healthcare practices and the emergence of a mid-layer that advances care delivery in the telehealth era. Even after a two-decade consolidation, business segments like home care, durable medical equipment, post-acute centers, and dentists are largely fragmented. Those areas can still benefit from supply and demand aggregation and workflow automation for improved efficiencies.

Beyond that, I am interested in the problems related to specific workflow functionalities handled by the legacy software systems and teaming up with entrepreneurs that tackle them one at a time. (Sapphire and A16z did an amazing job mapping out these companies.)

As we go through the MSO list, prior authorization, medical credentialing, payor contracting, and many other tasks are still primarily manual and contribute to HCP burnout regardless of whether practices operate in telehealth or brick-and-mortar. And now, we have seen a new wave of innovators addressing those problems incorporating the learnings from previous failures.

For example, Medallion provides PC services and management tools for all practices. Adonis detects RCM leakage in medical billing and coding by leveraging structured data in the EHRs. Our portfolio company, Serif Health, helps practices negotiate, manage, and track contracts backed by the most up-to-date pricing data across the country.

When we look at these function-oriented opportunities, the questions about market timing come from two folds - service quality inconsistency and the upstream “consolidation” that centralizes procurement decisions.

Due to the nature of those services, practice groups and PE firms would need to bring subject matter experts from outside the organizations to help them set up the workflow infrastructure and then be directly involved in completing the tasks.

Using contracting as an example, value-based care and alternative payment models have made business operations more complex. Operators now need to consider a spectrum of factors that may impact their financial health, such as assessing their scope of services, analyzing existing patient demographics, articulating health economics, etc. Partnering with good external experts can help a physician generate millions of dollars in profit over the coming years, while inappropriate contracting advice can cause a physician to lose money over the same time frame. By standardizing the services, a startup can quickly establish its brand.

Secondly, MSOs earn an economy of scale and help physicians improve operational efficiencies, yet they are not technology companies and will not build automation applications in-house. (We have also seen the early-stage no-code companies that may help address that.) Whether it’s through MSOs or the IPAs that assemble the service bundles for their customers/members, procurement decisions are purely based on sustaining the financial outcomes of each practice and made by business-savvy operators and physician executives.

Qi

(All above is my own view. Certain information contained here has been obtained from third-party resources.)